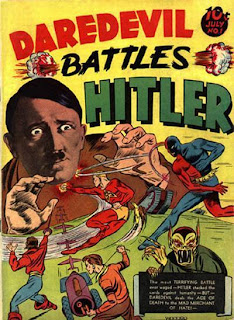

In the aftermath of yet another confrontation between Republicans and Democrats over budget policy and the promise of future conflicts, it is worthwhile to step back and consider the traditionalist appeal in the context of superhero comics. The “traditionalist appeal” in this context is the resurrection of classic characters in recent comicbook superhero stories. While the political debate rarely directly spills onto the comic page, the sense of the political environment does, and often with startling results. Whether pro-war sentiment associated with Captain America’s first appearance punching Adolf Hitler or a flurry of President Obama appearances, comics are not divorced from the political climate. Superhero comics and society inform each other, contextualizing values, delineating beliefs, and highlighting concerns associated with political debates. Thus, feminist critiques elicit change in the status and action of female characters, and concerns about racial equity trigger the introduction of diverse characters. While we can argue about the quality of these changes, the fact of these shifts is inescapable. Indeed, in an era of excess rhetoric, an analysis of the historical and cultural consistency in the superhero genre offers insights into the broader society. Uniquely linked to the United States’ social, political, and economic circumstances, superhero comics present a continuously updated narrative of the U.S. experience, shaping and being shaped by Americans’ views of themselves and the world.

With the editorial mandates from Marvel [The Heroic Age (THA)] and DC [Brightest Day (BD)] promising new status quo in both comic universes, questions about the conservative nature of comic stories are rising to the forefront. In THA and BD, order and at some level hope, have been re-established after disruptive periods. At Marvel, the storyline Dark Reign put Norman Osborn (the former villain Green Goblin) in control of global security, ushering in a time of villains masquerading as heroes and established heroes as outlaws. At DC, Blackest Night brought the Black Lanterns, the resurrected doppelgangers of friends and enemies who threatened life in the entire galaxy. Each story is built upon previous events over several years. This is crucial, since while individual writers are responsible for the their titles, every title exists under a thematic mandate coordinated by editors affecting the entire narrative universe. This is achieved through organized meetings where writers and editors plan key story and character arcs several months in advance. Thus, while comics are timely, they are not by definition reactionary. The decision to move the story in one direction or another is arrived at by a combination of factors: editorial mandate, writer input, character history, audience, and societal relevance all play a part in crafting the thematic event.

Since the September 11th terror attacks both major superhero comic publishers have provided stories that heighten the drama and put the spotlight on established characters. In a post-Cold War global community facing terrorist threats, heroism and villainy have added meaning, forcing superhero comics to re-focus their attention on defining heroic action. Incorporating the morally challenging circumstances of a “war on terror” and asking what heroes represent, comic properties have focused attention on community protection, individual agency, and moral ambiguity. This mandate, whether conscious or unconscious, has driven publishers toward a more synergistic storytelling style that adds to the impact of these thematic events. Superheroes are not just physically challenged; their code is suspect and their actions under scrutiny. Indeed, the trigger for Marvel’s Civil War event was the reckless behavior of superheroes working for a reality TV show and DC’s Infinite Crisis centered on the conflict created by modern-day “dark” heroes versus the “lighter” earlier generation of heroes. These events differ from the crossover stories so in vogue in 1980s and 1990s. While those events offered multiple chapters and many characters, they were often insular in effect (centered on particular character groups) and limited thematic effect (once over, everything tended to go back to “normal”). In contrast, the current pattern pushes the entire narrative universe to a different status quo with individual characters shifting based on internal and external factors while at the same time setting up the next event. On the whole, these stories have garnered positive fan reactions and sales successes. Nonetheless, criticism of creative decisions linked to these events has grown.

In both companies major characters have been killed and/or resurrected recently. This impact has been most pronounced in DC Comics where seminal characters such as Hal Jordan (the Green Lantern) and Barry Allen (Flash) have been brought back from the dead along with a host of other characters. At Marvel, Bucky Barnes, Captain America’s teen sidekick, was resurrected as the Winter Soldier, and Bobbi Barton, Mockingbird has returned. Recent commentary has characterized this approach as regressive storytelling at DC. The regressive nature of these stories is highlighted in the DC case by the whitening of second-generation legacy characters that had been re-imagined as racial minorities. The tradition of evolving the identity of iconic characters literally marks the shift from the Golden Age when superheroes were introduced and convention established to the Silver Age, when those same characters were re-design and new individuals took up the heroic legacy in the DC universe. These relationships remain integral as Golden Age characters are portrayed as mentoring young heroes in the pages of Justice Society of America (JSA). These seemly familial relationships make the legacy of heroic action symbolically a birthright. Not surprisingly, the effort to create successors for these characters that reflect greater ethnic diversity has been a point of contention for critics and fans.

This problem is personified by the recent resurrection of Steve Rodger, the former Captain America by Marvel. Given the movie scheduled for release in July, Steve Rodgers’ return to life was a forgone conclusion. Yet his return, which triggered an end to Osborn’s Dark Reign and ushered in THA, clearly demonstrates the symbolic power of the Golden Age character. In many ways, Captain America is the symbol of comics’ Golden Age. A World War II era soldier, the character signifies the moral conviction associated with the U.S. efforts against global fascism. Given this identification, his return definitively signaled the end of ethical ambiguity and strife connected with Dark Reign and redeemed the conflict associated the Civil War storyline. Yet, like Ronnie Raymond’s Firestorm or Ray Palmer’s Atom, Rodgers’ return displaced the agency and contribution of a racial minority. Luke Cage, who acted as leader of the New Avenger in his absence, was not killed or even ridiculed with Rodger’s return, yet Rodger represented legitimacy by his presence. In fact, his action upon returning was to “take the fight” to the bad guys, a move that other characters advocated but lacked the moral authority to carry out. Thus, Rodgers’ presence called into question the leadership provided by anyone who is not a white male authority figure tied to value forged in an era of "greatness." This point is further emphasized by the fact Rodgers did not take back the mantle of Captain America; instead he accepts the role of directing global security as himself. His former partner, Bucky Barnes, continues in the role of Captain America he took over when Rodgers was supposedly killed. Thus, the emphasis that Rodgers, the Golden Age hero is the stabilizing element is made clear.

Was this the intention? No, and charges of racism obfuscate the complexity of the problem. Captain America was created in a time of repressive racial and gender standards. His appearance and those of other Golden Age characters signify national pride, moral certainty, and social stability because they are products of a historical period when women, racial, and sexual minorities were silenced in the public sphere. Cultural artifacts from a period before Americans confronted the problems of access and equity that challenged the status quo of white male control, these characters link the reader to a mythical past.

This fact highlights a more profound sociocultural functionalism. While in the past, racial exclusion was a product of ignorance, today the decision to include diverse perspectives provides cover for a commoditization of identity. As theorist Slavoj Zizek explains, the acknowledgement and visible placement of the racial other allows for the rationalization of racial marginalization practice. Thus the drive to account for every identity serves to highlight the structural resistance to change.

Superheroes represent cherished values and reflect long held communal beliefs, and therefore the return of the “classic” version of a character reconnects the audience to an idyllic past. Umberto Eco’s analysis of Superman trivialized the importance of Clark Kent, suggesting that Kent served as a platform for the wish fulfillment symbolized by Superman. Yet, Kent offered the grounding to link Superman to a narrative of transformation at the heart of the U.S. experience. Superman can be theorized as a neo-fascist fantasy, but the suggestion ignores the creators’ ethnicity and life experience as second-generation Americans. The Superman/Clark Kent duality is more than an impulsive assimilative tale romanticized by émigrés for the communal collective.

Golden Age characters are admired because Americans did not question themselves in the period they were created. By bringing these characters back from the dead, creators circumvent the uncertainty forever linked to the agency asserted by women and minorities in the 1960s and 1970s. Thus, the redemptive roles assigned to Golden Age characters highlight a link between societal stability, whiteness, and masculinity while calling into question the legitimacy of racial and gender critiques of the status quo.

The loss of ethnic diversity highlights the intersection of culture and power, but it is not the goal. The restoration of social stability, which coincides with the return of Golden Age heroes, emphasizes the culturally splintered communal present-day is not as good as the past. Ironically, the past being referenced is not real. Labor strife, gender challenges, struggle for civil rights, and calls for equity have existed throughout U.S. history. The reverential look back omits those conflicts.

Superhero comics actualize the anxiety that values that guided the United States in the past have been sacrificed for gender and/or racial equality. This is not a case of the character representing racism, instead it is something I call iconic memory, using an object as a placeholder for an imagined past. Divorced from the real, yet referencing it, comic characters allow creators and readers to selectively invoke the past. Iconic memory interposes a fantasy for the reality. By focusing on the artifacts of our collective imagination, we can avoid the facts that disrupt or sense of order in contemporary society. In an era of globalization, when an amorphous war on terror has replaced Cold War certainties, enemies can be foreign, domestic, or neither. In this world, the desire for heroes we can believe in is greater. Fearing a permanent loss of prosperity, facing challenges to “normative” social practice, and fearing attack from faceless enemies, superheroes from the 1930s and 1940s offer reassurance that the core tenets of the United States remain true. It is this fact that drives the decision to return “classic” characters to the forefront of the DC and Marvel Universes. Conservatism in comics, like conservatism in the broader society, reassures us by providing symbolic reminders of past glory that foreshadow future promise.

Comments